Butterstream Gardens – Background

This garden is no longer open, and has been incorporated into a housing estate. However, I decided to post an updated version of my old TrimTown Butterstream page to keep it “alive”. I had always enjoyed visiting – and it was truly impressive when at its peak. It was described as the Hidecote or Sissinghurst of Ireland. The designer – Jim Reynolds – is also responsible for some other Irish gardens such as those in the Merrion Hotel Dublin (which has another Trim connection – being the birthplace of the Duke of Wellington), Ballyfin and Ballymaloe Ornamental Fruit Garden.

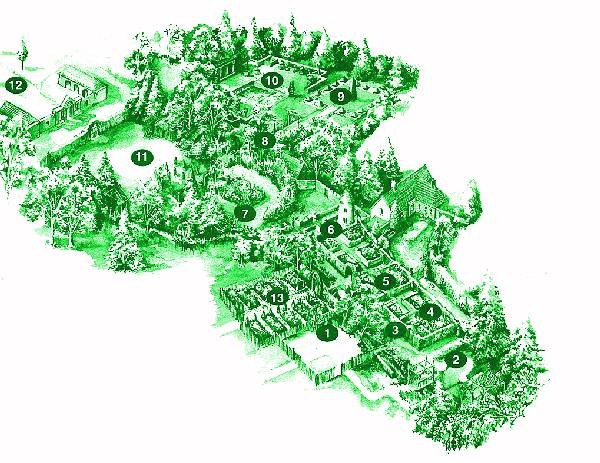

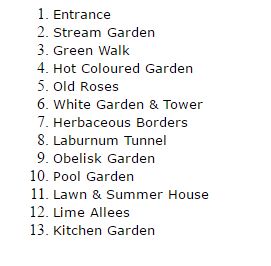

Map of Butterstream Gardens – as it was

The Butterstream Story

Butterstream Gardens has been closed for many years. It was built up from nothing over a period of twenty years or more through the work of one man – Jim Reynolds. Here, in his own words, he tells how it came about :

It started innocently enough. There was no grand vision of Arcadia, no hint of an all-absorbing passion, no trumpets sounded in my ear – just the heaving and thud of a piece of clay being double-dug in preparation for the reception of a dozen hybrid tea roses.

This irrational urge to possess a few roses had come quite suddenly. While I had enjoyed helping to plant wallflowers and summer bedding as a child, I had during schooldays been a most reluctant gardener, baulking at the prospect of involvement with anything requiring physical exertion. By my early twenties the prospect of a little light dabbling in the garden seemed attractive enough: pruning, dead-heading and a spot of gentle weeding would not be too demanding, I thought.

I soon became a garden visitor. Mount Stewart, Birr Castle and Ilnacullin – all on a suitable grand scale -were favourite destinations. In Britain, Crathes and Sissinghurst provided inspiration. My horizons began to expand quickly and I realised that even a young chap with nothing more than a dozen roses could learn an immense amount about the principles of design, layout and planting.

These new-found notions and theories would have been of little use had there not been some ground on which to make a garden. I was particularly fortunate in growing up on a farm, so mere was some space available for these early horticultural experiments and nobody particularly objected to my enclosing the corner of a field. As I became more ambitious (more foolish, my friends thought), the fence migratedfarther and farther out into the field.

From the early 1970s a series of small compartments evolved. The site, being long and narrow, particularly lent itself to division, and as I began to collect plants and to concentrate on matters of design it seemed most reasonable and logical to devote different areas to particular plants or colour schemes.

In the beginning my ventures were greatly enlivened by the frequent visits of stampeding cattle or by browsing horses whose special delight was to pull recently planted shrubs and trees from the ground, chew on them a bit and then discard them. Other rural delights missed by town gardeners were the visits of the rabbits and hares. They shared things very fairly.

Knowing nothing, I naively assumed that I could grow anything that took my fancy: a few camellias, acacias, lots of rhododendrons, an embothrium or two. The possibilities seemed endless, or so the horticultural literature seemed to imply. After all, this is Ireland, we have a mild climate and we are: renowned for our Robinsonian gardens It did not take very long to learn that the Irish midlands are not suited at all to these things: the ungrateful persisted in dying. The soil is a heavy limestone clay and there is generally hard winter frost.

These setbacks did little to disenchant me, but were, I soon realised, a decided advantage and saved me from the dreaded fate of making a rhododendron garden supplemented with conifers and heathers for added boredom. I thoroughly agree with the late Russell Page’s summary of most large rhododendron collections as being as artistically interesting as a wallpaper catalogue. Instead I came to the joys of roses old and new – enormous and sprawling like the delicious pink ‘Belvedere Rambler’ (common in old Irish gardens) or the delectable little Edwardian ‘Natalie Nypels’ – flowering shrubs and small trees, foliage plants and most importantly of all the unending range and variety of herbaceous perennials. There were choice and tasty pickings to be found in old gardens, particularly m old walled gardens around the country: shrub roses that had long ago lost their names and lots of tantalising herbaceous plants. The candelabra primulas, ‘Lissadel Pink’ and ‘Asthore’; the startling alpine thistle, Eryngium alpinium ‘Slieve Donard’; and numerous choice old crocosmias and campanulas are just a few almost forgotten plants which were to be found. As a plant collector it would be so easy to end up with a jumble of horticultural misfits and oddities and no doubt some would find comets here which begin to resemble cabinets of curiosities I try to be rigid on matters of design and of colour, always bearing in mind that a garden should be an aesthetic or even sensual experience with a careful buildup of drama and excitement, interspersed with pauses leading to new expectations and eventually to a suitably timed climax. While each garden room at Butterstream is complete in itself with its own particular mood and planting, the eye is drawn onwards by the sight of a gate, an urn or a pavilion until the final comer is rounded and the grand finale comes into view. This is a small Tuscan temple reflected in a lily pool set in a wide pavement and surrounded by formal lines of box and terracotta pots, providing an evocation of a different world – a villa garden in Pompeii.

After 20 years of five to nine gardening (the best part of the day from nine to five was spent as an archaeologist of sorts), I decided that the garden should begin to keep me. Having worked single- handed for so long it was time to have a little help and this would be paid for by opening to the public, It is rather nice to note that the Good Gardens Guide has been pleased to honour my efforts with their highest accolade, two stars. Some think that my head will never again fit through the door.)

Nature must take much of the credit. Many things have succeeded in spite of me and the overall result has been beyond my expectations. My hope is that visitors will be inspired to be more adventurous and daring in their own gardens. It really is the greatest fun.

Jim Reynolds