Background

William Makepeace Thackeray was an English novelist, famous for his satirical works. Apart from the one discussed here, he also wrote “The Luck of Barry Lyndon” which was later filmed by Stanley Kubrick as Barry Lyndon (and happens to be one of my own favourite films).

In 1842, he visited Ireland and wrote a book based on his travels – “The Irish Sketch Book” – a precursor to the Lonely Planet guide, with lots of ill-tempered reviews. He arrived at Dún Laoghaire (then Kingstown) and later visited Trim, but didn’t much like it. Although his style of writing is probably intended to be tongue-in-cheek and humorous, it can appear to be a bit patronising at times.

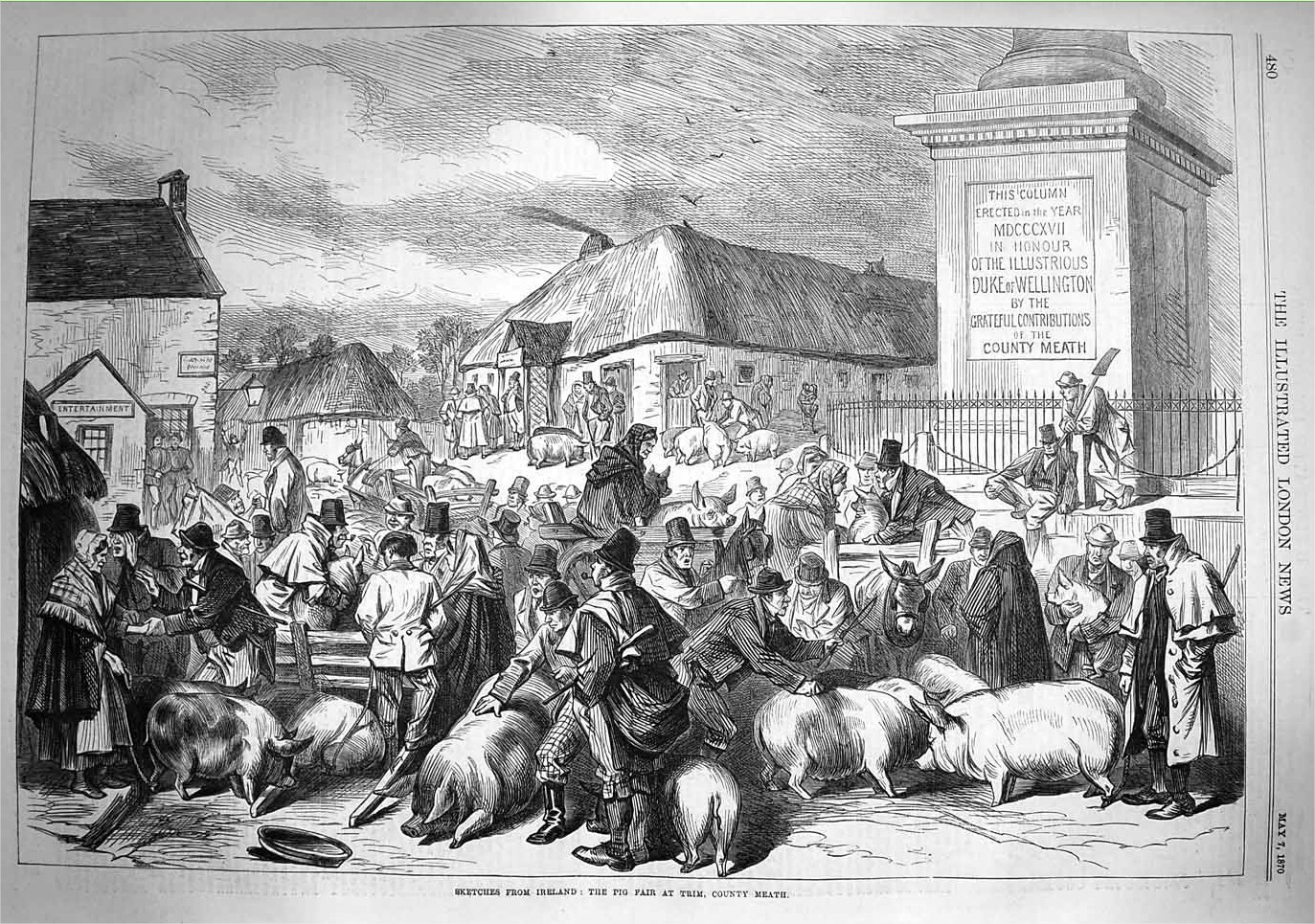

The image at the top of this post comes from about 30 years after his visit. However, I doubt if the scene was much different then – in fact it’s still very recognisable even now (with The Steps/Leonards pub in the LHS-background).

Two Extracts from “The Irish Sketch Book”

Kingstown-Shelbourne Hotel

When everybody was awakened at five o’clock by the noise made upon the removal of the mail-bags, there was heard a cheerless dribbling and pattering overhead, which led one to wait still further until the rain should cease. At length the steward said the last boat was going ashore, and receiving half a crown for his own service (which was the regular tariff), intimated likewise that it was the custom for gentlemen to compliment the stewardess with a shilling, which ceremony was also complied with. No doubt she is an amiable woman, and deserves any sum of money. As for inquiring whether she merited it or not in this instance, that surely is quite unfair. A traveller who stops to inquire the deserts of every individual claimant of a shilling on his road, had best stay quiet at home. If we only got what we deserved–heaven save us–many of us might whistle for a dinner.

A long pier, with a steamer or two at hand, and a few small vessels lying on either side of the jetty; a town irregularly built, with many handsome terraces, some churches, and showy-looking hotels; a few people straggling on the beach; two or three cars at the railroad station, which runs along the shore as far as Dublin; the sea stretching interminably eastward; to the north of the Hill of Howth, lying grey behind the mist, and, directly under his feet, upon the wet, black, shining, slippery deck, an agreeable reflection of his own legs, disappearing seemingly in the direction of the cabin from which he issues: are the sights which a traveller may remark on coming on deck at Kingstown pier on a wet morning–let us say on an average morning; for according to the statement of well-informed natives, the Irish day is more often rainy than otherwise. A hideous obelisk, stuck upon four fat balls, and surmounted with a crown on a cushion (the latter were no bad emblems perhaps of the monarch in whose honour they were raised), commemorates the sacred spot at which George IV. quitted Ireland. You are landed here from the steamer; and a carman, who is dawdling in the neighbourhood, with a straw in his mouth, comes leisurely up to ask whether you will go to Dublin? Is it natural indolence, or the effect of despair because of the neighbouring railroad, which renders him so indifferent? He does not even take the straw out of his mouth as he proposes the question–he seems quite careless as to the answer.

He said he would take me to Dublin “in three quarthers,” as soon as we began a parley. As to the fare, he would not bear of it–he said he would leave it to my honour; he would take me for nothing. Was it possible to refuse such a genteel offer? The times are very much changed since those described by the facetious Jack Hinton, when the carmen tossed up for the passenger, and those who won him took him; for the remaining cars on the stand did not seem to take the least interest in the bargain, or to offer to overdrive or underbid their comrade in any way.

Before that day, so memorable for joy and sorrow, for rapture at receiving its monarch and tearful grief at losing him, when George IV. came and left the maritime resort of the citizens of Dublin, it bore a less genteel name than that which it owns at present, and was called Dunleary. After that glorious event Dunleary disdained to he Dunleary any longer, and became Kingstown henceforward and forever. Numerous terraces and pleasure-houses have been built in the place–they stretch row after row along the banks of the sea, and rise one above another on the hill. The rents of these houses are said to be very high; the Dublin citizens crowd into them in summer; and a great source of pleasure and comfort must it be to them to have the fresh sea-breezes and prospects so near to the metropolis.

The better sort of houses are handsome and spacious; but the fashionable quarter is yet in an unfinished state, for enterprising architects are always beginning new roads, rows and terraces: nor are those already built by any means complete. Beside the aristocratic part of the town is a commercial one, and nearer to Dublin stretch lines of low cottages which have not a Kingstown look at all, but are evidently of the Dunleary period. It is quite curious to see in the streets where the shops are, how often the painter of the signboards begins with big letters, and ends, for want of space, with small; and the Englishman accustomed to the thriving neatness and regularity which characterise towns great and small in his own country, can’t fail to notice the difference here. The houses have a battered, rakish look, and seem going to ruin before their time. As seamen of all nations come hither who have made no vow of temperance, there are plenty of liquor shops still, and shabby cigar shops, and shabby milliners’ and tailors’ with fly-blown prints of old fashions. The bakers and apothecaries make a great brag of their calling, and you see MEDICAL HALL, or PUBLIC BAKERY BALLYRAGGET FLOUR STORE (or whatever the name may be), pompously inscribed over very humble tenements. Some comfortable grocers’ and butchers’ shops, and numbers of shabby sauntering people, the younger part of whom are barelegged and bareheaded, make up the rest of the picture which the stranger sees as his car goes jingling through the street.

After the town come the suburbs of pleasure-houses; low, one-storied cottages for the most part: some neat and fresh, some that have passed away from the genteel state altogether, and exhibit downright poverty; some in a state of transition, with broken windows and pretty romantic names upon tumbledown gates. Who lives in them? One fancies that the chairs and tables inside are broken, that the teapot on the breakfast-table has no spout, and the table-cloth is ragged and sloppy; that the lady of the house is in dubious curl-papers, and the gentleman, with an imperial to his chin, wears a flaring dressing-gown all ragged at the elbows.

To be sure, a traveller who in 10 minutes can see not only the outsides of houses, but the interiors of the same, must have remarkably keen sight; and it is early yet to speculate. It is clear, however, that these are pleasure-houses for a certain class; and looking at the houses, one can’t but fancy the inhabitants resemble them somewhat. The car, on its road to Dublin, passes by numbers of these–by more shabbiness than a Londoner will see in the course of his home peregrinations for a year.

The capabilities of the country, however, are very great, and in many instances have been taken advantage of: for you see, besides the misery, numerous handsome houses and parks along the road, having fine lawns and woods; and the sea is in our view at a quarter of an hour’s ride from Dublin. It is the continual appearance of this sort of wealth which makes the poverty more striking: and thus between the two (for there is no vacant space of fields between Kingstown and Dublin) the car reaches the city. There is but little commerce on this road, which was also in extremely bad repair. It is neglected for the sake of its thriving neighbour the railroad; on which a dozen pretty little stations accommodate the inhabitants of the various villages through which we pass.

The entrance to the capital is very handsome. There is no bustle and throng of carriages, as in London; but you pass by numerous rows of neat houses, fronted with gardens and adorned with all sorts of gay-looking creepers. Pretty market-gardens, with trim beds of plants and shining glass-houses, give the suburbs a riante and cheerful look; and, passing under the arch of the railway, we are in the city itself. Hence you come upon several old-fashioned, well-built, airy, stately streets, and through Fitzwilliam Square, a noble place, the garden of which is full of flowers and foliage. The leaves are green, and not black as in similar places in London; the red brick houses tall and handsome. Presently the car stops before an extremely big red house, in that extremely large square, Stephen’s Green, where Mr. O’Connell says there is one day or other to be a Parliament. There is room enough for that, or for any other edifice which fancy or patriotism may have a mind to erect, for part of one of the sides of the square is not yet built, and you see the fields and the country beyond.

This then is the chief city of the aliens.–The hotel to which I had been directed is a respectable old edifice, much frequented by families from the country, and where the solitary traveller may likewise find society: for he may either use the “Shelburne” as an hotel or a boarding-house, in which latter case he is comfortably accommodated at the very moderate daily charge of six-and-eightpence. For this charge a copious breakfast is provided for him in the coffee-room, a perpetual luncheon is likewise there spread, a plentiful dinner is ready at six o’clock: after which there is a drawing-room and a rubber of whist, with tay and coffee and cakes in plenty to satisfy the largest appetite. The hotel is majestically conducted by clerks and other officers; the landlord himself does not appear, after the honest, comfortable English fashion, but lives in a private mansion hard by, where his name may be read inscribed on a brass-plate, like that of any other private gentleman.

Trim

The Meath landscape, if not varied and picturesque, is extremely rich and pleasant; and we took some drives along the banks of the Boyne-to the noble park of Slane (still sacred to the memory of George IV., who actually condescended to pass some days there), and to Trim–of which the name occurs so often in Swift’s Journals, and where stands an enormous old castle that was inhabited by Prince John. It was taken from him by an Irish chief, our guide said; and from the Irish chief it was taken by Oliver Cromwell. O’Thuselah was the Irish chief’s name no doubt.

Here too stands, in the midst of one of the most wretched towns in Ireland, a pillar erected in honour of the Duke of Wellington by the gentry of his native county. His birthplace, Dangan, lies not far off. And as we saw the hero’s statue, a flight of birds had hovered about it: there was one on each epaulette and two on his marshal’s staff. Besides these wonders, we saw a certain number of beggars; and a madman, who was walking round a mound and preaching a sermon on grace; and a little child’s funeral came passing through the dismal town, the only stirring thing in it (the coffin was laid on a one-horse country car–a little deal box, in which the poor child lay–and a great troop of people followed the humble procession); and the inn-keeper, who had caught a few stray gentlefolk in a town where travellers must be rare; and in his inn-which is more gaunt and miserable than the town itself, and which is by no means rendered more cheerful because sundry theological works are left for the rare frequenters in the coffee-room–the inn-keeper brought in a bill which would have been worthy of Long’s, and which was paid with much grumbling on both sides.

It would not be a bad rule for the traveller in Ireland to avoid those inns where theological works are left in the coffee-room. He is pretty sure to be made to pay very dearly for these religious privileges.

You can view a full version of the book online here